Not too long ago the current member of the first presidency,

Dallin H Oaks, gave a talk entitled, Where

will this lead? He discussed the importance of basing current decisions on

future events.

The setting was a beautiful college campus. A crowd of young students was seated on the grass…[T]hey were watching a handsome tree squirrel with a large, bushy tail playing around the base of a beautiful hardwood tree. Sometimes it was on the ground, sometimes up and down and around the trunk…

Stretched out prone on the grass nearby was an Irish setter. He was the object of the students’ interest, and the squirrel was the object of his. Each time the squirrel was momentarily out of sight circling the tree, the setter would quietly creep forward a few inches and then resume his apparently indifferent posture. This was what held the students’ interest. Silent and immobile, their eyes were riveted on the event whose outcome was increasingly obvious.

Finally, the setter was close enough to bound at the squirrel and catch it in his mouth. A gasp of horror arose, and the crowd of students surged forward and wrested the little animal away from the dog, but it was too late. The squirrel was dead.

Personally, I would have let nature take its course. Any squirrel that wasn’t savvy enough to dodge a dog would probably ruin the gene pool anyway. But President Oaks then discussed the point of this true-life parable, not too different from the parable I offered:

Anyone in that crowd could have warned the squirrel at any time by waving his or her arms or crying out, but none did. They just watched while the inevitable outcome got closer and closer. No one asked, “Where will this lead?” When the predictable occurred, all rushed to prevent the outcome, but it was too late. Tearful regret was all they could offer…

[This] applies to things we see in our own lives and in the lives and circumstances around us. As we see threats creeping up on persons or things we love, we have the choice of speaking or acting or remaining silent. It is well to ask ourselves, “Where will this lead?” Where the consequences are immediate and serious, we cannot afford to do nothing. We must sound appropriate warnings or support appropriate preventive efforts while there is still time.

What astounded me about this story is how closely it parallels the arguments that I’ve been making for years. The late 17th century theorist Samuel Puffendorf described the principle as a right to defend yourself from a “charging assailant with sword in hand.” The Book of Mormon implies this principle when it says Nephites were taught “never to raise the sword” except to preserve their lives (Alma 48:14). This is commonly assumed to mean defense. But there is a time between raising a sword and swinging the sword. As well as a time before swinging a sword and striking someone with a sword. Thus, defense doesn’t begin when the sword hits you or hits you three times as some inappropriately apply Doctrine and Covenants 98, but defense begins when the sword is raised but hasn't yet struck. Or as summarized by Grotius: when the attack is commenced but not carried out.

The basic principle was best explained by the early modern

scholar, and founder of international law, Hugo Grotius. He described the

principles of intent, means and imminency. This applies personally and

intentionally. A short time ago Israel saw thousands of Hezbollah rockets

pointed at them. They had an avowed enemy with an expressed intent to

exterminate Israel. The means consisted of thousands of rockets pointed

at Israel. Those rockets were ready to launch, and Israel had solid

intelligence that the launch was imminent. So, Israel exercised their

God given right to defend themselves from a raised sword.

Personally, this is just as applicable. A crazed men enters

the subway. He yells about his intent that he wants to stab people and doesn’t

care if he goes to jail. He waves around the knife in his hand. And he is so

deranged an attack seems imminent. I’m not making any of this up, this was the Neely

subway attack. Thankfully, a brave Good Samaritan that deserves a medal put

the man in a choke hold and prevented an attack. He and other subway passengers

didn’t stand around and say to themselves, “this is really dangerous, lets see

where he’s going with this.” They didn’t wait until the attack was carried out, in

which they or others would have already been hurt. They acted preemptively.

Even comedians understand this principle! A young mother was

at a sketchy motel in the movie, Manos: The Hands of Fate. When the strange

motel employee, Torgo, started palming her hair the RiffTrax comedian jokingly

added her line, “This is

super creepy but I’ll just stand right here and see where he’s going with this.”

And now, I found that one of the leaders of the church

understands the principle as well. “Where the consequences are immediate and

serious, we cannot afford to do nothing. We must sound appropriate

warnings or support appropriate preventive efforts while there is still time.”

This, dear readers, is the essence of justified preemptive

war. I’ve been accused of being a warmongering, insane, deranged anti-Christ

and war criminal with a stench of death for espousing these views. All I want is for people to be safe and

exercise their God given rights to defense. Now I find this view espoused by

President Oaks.

This principle has one more ironic note. Dallin H. Oaks is

often quoted by peace advocates for his story about stopping a mugging by

expressing tenderly, fatherly care.[1]

The lesson gathered is somewhat misplaced, since an approaching bus distracted

the mugger and seemed to have at least as much dissuasive power as Oak’s

expressions of “assertive love.” On top of that, it’s rather condescending of

pacifists to take one story and make it a general rule that should apply to

everyone. Moreover, Dallin Oaks himself recognizes the need for preemptive

action or else he wouldn’t have shared the parable of the squirrel years later.

There is a great deal more evidence for preemptive war than

many people realize. It has a strong theoretical basis based on solid reasons. The

concept has implied scriptural support through Alma 48:14 and numerous

other scriptures or stories. This includes Mosiah 9:1, the events after Alma

26:25, Helaman 1, Helaman 2, and even a careful reading of supposedly disqualifying

verses like 3rd Nephi 3:21 or Mormon 4:4 support the practice. It

works in the practical world ranging from the subway to missiles and it’s been practiced

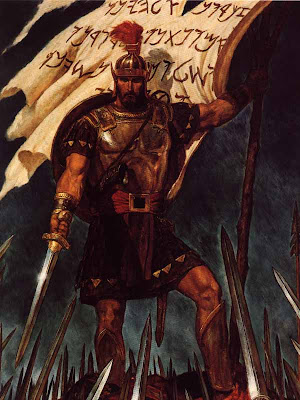

by everyone from Epaminondas to Moroni. Finally, its fundamental truth is

explained by a supportive Dallin Oaks. We must ask where something will lead. When

the cost of inaction is too dangerous, we are not only allowed, but commanded

to take appropriate preemptive action.

[1] Patrick

Mason and David Pulsipher, Proclaim Peace: The Restoration’s Answer to an Age

of Conflict, Maxwell Institute, Deseret Book, 2021) 109-113.