Wednesday, July 22, 2009

Guest Writer: Roger on Hill Cumorah Order of Battle

I also have some good developments to announce as well. I have been contacted by several people asking for my opinion on various items. I have a new card game called "character match" that I need to look at. One reader and frequent commenter has mentioned a historical fiction novel that he plans to send me for review. The result will probably be a multi part series here and hopefully make it on the cover! And I received an email from Roger Magneson which is the subject of this post.

Roger graduated from West Point Academy, which already made me jealous, and he recently got his MLS from Emporia State. He recently wrote an article highlighting three principles of war within the book of Mormon. The one I wanted to highlight in this post comes from his provacative interpretation of the casualty figures given for the final Nephite battle at Cumorah. I won't steal his thunder by bloviating about the topic, but I did want to highlight that a common criticism of the Book of Mormon concerns its highly unrealistic numbers. I rebuffed that critique in The problem with Numbers

where I also recognized the need for additional research and analysis. Without further ado here is Roger's argument:

Units of the United States Army have names that have come down through history and through several countries. Terms such as squad, platoon, company, battalion, brigade, division, etc. are known to most people even if they are uncertain about how many soldiers comprise each. The size of units in the United States Army is determined by acts of Congress. During the American Civil War, for example, an infantry regiment consisted of 10 companies of roughly 100 men each. One thing is certain, however: at any given moment, not every position in a unit is filled. Consider the First Minnesota Infantry Regiment at the Battle of Gettysburg. Since we know this is an infantry regiment, we know that it is comprised of approximately 1,000 men. However, on 2 July 1863, at Gettysburg, the First Minnesota had been reduced by casualties to 262 men. On that day, 215 more were killed or wounded.David ben Jesse was made a captain over a thousand by Saul the King (1 Samuel 18:13) and of course modern Israel in its trek to the Great Basin had captains of tens, fifties, and hundreds similar to ancient Israel (D&C 136:3).

Not only were the numbers descriptive of the size of the unit, but as Dr. Hugh Nibley points out the number was also the name of the unit. In discussing Nephi’s reference to Laban’s fifty instead of tens of thousands (1 Nephi 4:1), Dr. Nibley states: the military forces are always so surprisingly small and a garrison of thirty to eighty men is thought adequate even for big cities. It is strikingly vindicated in a letter of Nebuchadnezzar, Lehi’s contemporary, wherein the great king orders: “As to the fifties who were under your command, those gone to the rear, or fugitives return to their ranks.”

Commenting on this Offord says, “In these days it is interesting to note the indication here, that in the Babylonian army a platoon contained fifty men”; also we might add, that it was called a “fifty”—hence, “Laban with his fifty.” Of course companies of fifty are mentioned in the Bible, along with tens and hundreds, etc., but not as garrisons of great cities and not as the standard military unit of this time (Nibley, 1988, p. 127.)

Now consider Cumorah, the final battle of the Lehite nations. Beginning in A.D. 375, the Nephites, not the army, but the entire Nephite nation was being driven before the Lamanite armies (Mormon 4:22). In A.D. 384, Mormon in a letter to the Lamanite king asks if he, Mormon, can gather the Nephite nation to battle at Cumorah, which is granted by the Lamanite king (Mormon 6:2-3). Within a year all the people are gathered in except a few who flee to the south country and a few who defect to the Lamanites (Mormon 6:15). At the end of the first day’s fighting, Mormon gives a list by name of 13 commanders and their ten thousand who had fallen, Mormon and Moroni being the exceptions, and then states there were 10 more commanders with their ten thousands who had fallen (Mormon 6:11-15) for a total of approximately 230,000 dead. Note that the name of the unit is ten thousand. Taking a cue from the regiments of the American Civil War, Nephite units might have been called, for example, the First Zarahemla Ten Thousand, the Second Zarahemla Ten Thousand, the First Bountiful Ten Thousand, and so forth.

The problem is this: the Nephite people had been conducting a running and losing battle with the Lamanites for 10 years, and while there may have been at one time 23 units called “ten thousand” in the Nephite army, when the Nephites gathered to Cumorah they were gathering everyone, including women and children (Mormon 6:7). It is highly unlikely that the 23 “ten thousands” were anywhere near full strength in terms of fighting men. Could the difference have been made up of women and children? The record is silent on this point, but knowing the desperate nature and the finality of the fight at Cumorah, it is highly probable that the women and children would fight in the ranks in preference to being captured by the Lamanites. However, even with women and children in the ranks I could not believe the ten thousands were at full strength. In my experience in the military I have never seen a military unit at full strength. Considering that the Nephites had just completed a running war of ten years, I would guess the Nephite ten thousands were anywhere from mere token units, as the First Minnesota, to at most 50% strength.

I appreciate Roger sending me his research, and I'm honored that so many believe I have something meaningful to offer in the field of Mormon studies. I will continue my attempts to deliver. In that vein I recommend my post called Myriads of Soldiers that discusses the number of a unit equalling its name.

I should also point out that this is the kind collaborative effort that I wish to stimulate in my attempts at a warfare symposium. Thank you for your patience. As always, I invite comments and look forward to seeing them.

Saturday, May 23, 2009

Myriads of Soldiers

Xenophon's book, The Anabasis, recounts the story of Ten Thousand Greek soldiers that were trapped deep in Persian territory and had to fight their way out. In that book, the Greek root of the word myriad actually refers to a Greek unit of ten thousand men. I only mention it because today we use myriad in an adverbial sense, such as "the myriad fish in the ocean". And it can also be used as a noun, as in the "myriads of soldiers". In both instances the original usage of myriad, meaning ten thousand is lost and replaced with an approximate use of the word.

Now I can see a case where the Book of Mormon uses a reformed Egyptian word that has colloquial meaning, but Joseph Smith translates the term literally into a number. It would be as though a modern translator took the opposite of what happened to myriad, they took a phrase that now means "many people" and literally translated it to ten thousand.

Thus there is one more nuance added to our understanding of numbers in the Book of Mormon. There is evidence from classical western sources that a specific term for a military unit can change meaning through time. I appreciate Firetag for raising the original question and I hope to see some of his research soon.

Saturday, May 25, 2013

Military Participation Ratio and Wrong Numbers

[These are some impromptu remarks I made recently on a discussion board. As such it doesn't have a polished introduction and conclusion.]

Do wrong numbers destroy the truthfulness of The Book of Mormon?

The answer is a resounding no. I explained a few reasons why in this post about millions. But there are more. For example, Chinese writers would want to highlight how the previous dynasty lost the Mandate of Heaven, so they would inflate the size of the bad last emperor's army. Ancient historians often wrote not to tell what happened, but with a specific moral purpose. So they didn't have the same scruples about bending facts to fit their story. Brant Gardner even discussed how one set of deaths in The Book of Mormon followed a same double same double pattern. (Alma 2:19) This could be a coincidence, or it had some sort of symbolic power. This is similar to the modern "I've told you a million times" or Jesus using the phrase "seven times seventy." So if The Book of Mormon has the same problem listing exact number for deaths on battle or the size of armies, as other historical documents this puts it in good company.

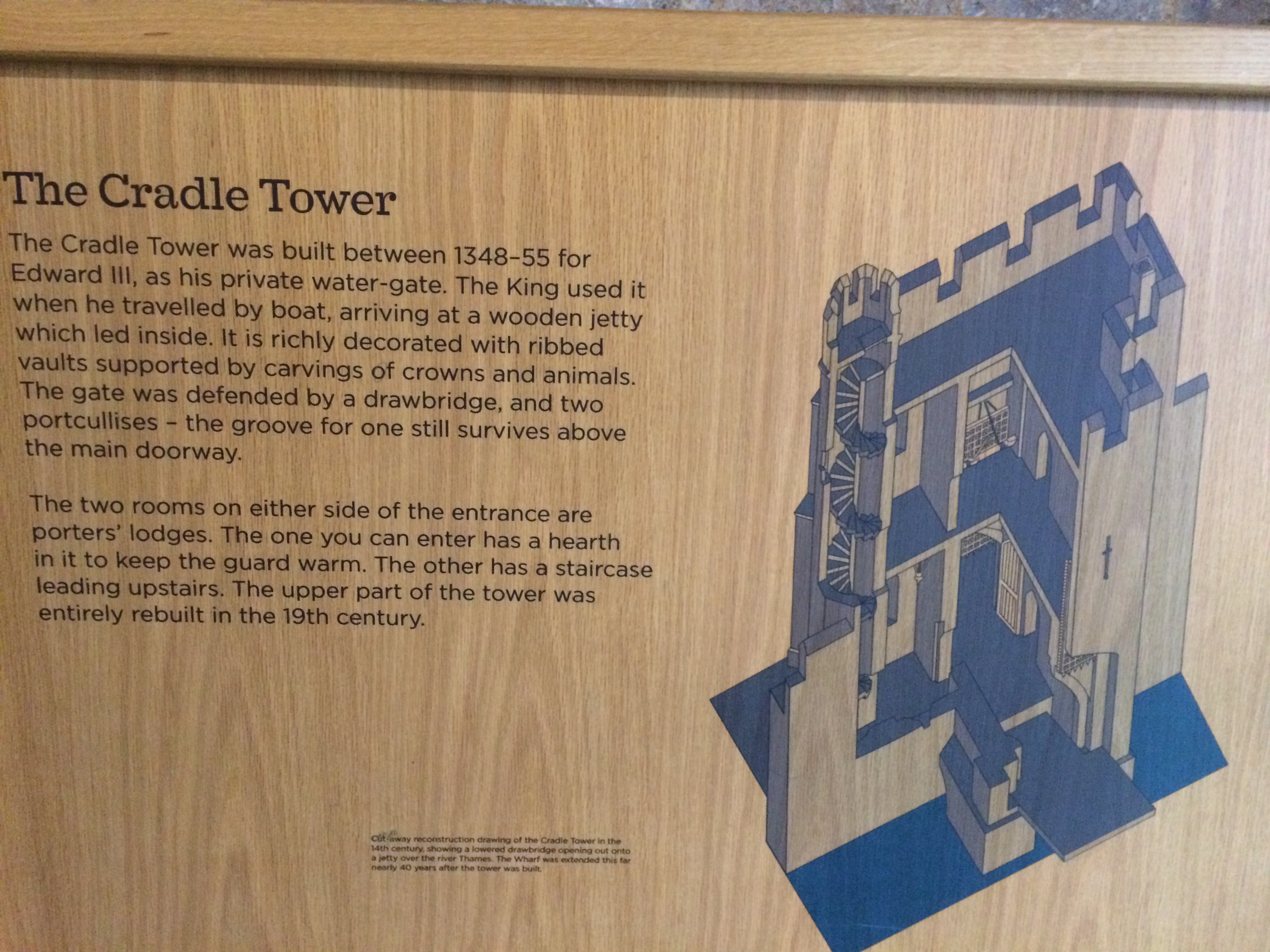

This gets even more confusing because some ancient words stood for a number and a unit. But the size of that military unit could change. Centurion means one soldier of one hundred. But by the late Roman Empire, Centuries only had 80 people. Myriad is another ancient word that have this problem. So when I see "ten thousand" listed so often in Mormon chapter 6 I start to that is a unit name and not necessarily a number. For example, by the end of the American Civil War some units in Lee's Army of Northern Virginia had only a fraction of their normal strength. (They did this out of pride because units didn't want to retire their colors and consolidate.) So if a general is listed as having "his ten thousand" there is a strong chance this refers to a unit name rather than a number. It is discussed in a bit greater detail in the first two posts here: http://mormonwar.blogspot.com/search?q=ten+thousand

Further, I find it odd that Mormon would begin his war of survival with 30,000 soldiers. (Mormon 2:42) But after many years of defeats, defections, and the loss of their capital city and lands, he had 7 times that number in the final battle. (Just from a logistical point of view I have a problem with this increase.) But when you look at the MPR this supposedly sudden increase in size makes more sense. The Military Participation Ratio is a formula historians use to figure out army and population sizes and other items. Basically its how many soldiers a society can muster for war. The high limit is usually 15% of the population can be mobilized for war. (Though ancient Sparta could muster about 25%.) For example, historians estimate that the U.S. MPR for WWII was 12%. So 30,000 would be about 15% of 200,000. This is close to the number listed in the final battle. This being the number of the total population gains strength when we read Mormon 6:7. If you read it carefully it sure seems to suggest that the order of battle included women and children. Towards the end of any war a nation scrapes the bottom of the barrel to fill out their army.

So even if the numbers are exaggerated by Mormon, or translated as numbers instead of units by Smith, or if these were unit names that didn't exist at their full strength, or the total population it doesn't matter. Having a problem with numbers puts it in good historical company, and a 30,000 man army and an ethnic group numbering about a quarter million is believable. There is both internal evidence and historical precedence for each view. Keep in mind that the writers in The Book of Mormon often complained about being "almost surrounded." Alma 22:29 In Mosiah25:2-3 we read that the Nephites were only about a quarter of the population of the Lamanites. (There are other verses that suggest the Nephites were a political minority, as well as significant outside sources from Mesoamericanists that often describe a small political elite ruling a much larger population, but this is getting on another topic.)

Monday, December 14, 2009

Fatal Terrain in The Book of Mormon

Alma 56:28- And also there were sent two thousand men unto us from the land of Zarahemla. And thus we were prepared with ten thousand men, and provisions for them, and also for their wives and their children.

Likely explanations of Alma 56:28 also include a psychological motivation for the inclusion of women and children on a border city. Classic Chinese military theorists such as Sun-Tzu wrote that when a commander “[throws] his soldiers into a place from which there is nowhere to go, they will die rather than flee. When they are facing death, how can one not obtain the utmost strength from the officers and men?”[1] Historian David Graff called this a “psychological trigger” that commanders would employ in order to “stimulate” a soldier that would otherwise act indifferently.[2] In this case, the deployment of both soldiers and family could be viewed as a governmental policy designed to help conscripts fight with greater élan. Moroni could have thought that having the family of fighting soldiers live in the threatened city would spur the Nephite armies more than leaving the family safely at the capital. In support of this argument, Moroni hinted at the apathy associated with staying in the capital when he condemns the civil government for lack of effort.[3] Plus, previous events in the Book of Mormon contribute to the deadly combination of family and military service. The soldiers of King Noah burned him at the stake for his order to abandon their families and his refusal to allow them to return.[4] This event could be an abnormal exception, or it could be the logical and expected sequence of events for soldiers that are forced to abandon their families by order of the government. The Nephites abnormal behavior of burning their king could be considered a psychologically motivated event based on familial concern.

The foregoing explanation assumes that the average Nephite soldier needed this boost, and that the government and Moroni would be harsh enough to place families in a dangerous situation simply to incite greater effort. This would also seem to counter the ideological imperative stated in the Title of Liberty- that the rights of their family trump the right of the Nephite leadership to use them as psychological props. A compromise position could consist of Moroni including the wives and children of soldiers in the field armies for their pragmatic benefits of increased morale, more efficient use of combat power and ideological purity; with the unstated or even unintentional benefit of a psychological trigger as well.

Thanks for reading. What do you think? Can you think of other examples that display this kind of military thinking? Are there any contradictory examples in The Book of Mormon?

***Sources***

1. Ralph Sawyer trans. The Seven Military Classics of Ancient China (New York: Basic Books, 1993.)179, also see footnote 162.

2. David Graff Medieval Chinese Warfare 300-900 (London and New York: Routledge Press, 2002) 169.

3. Alma 60:21-22.

4. Mosiah 19: 16-20.

Friday, April 20, 2018

Revisiting Alma 56:28 and Women in Combat

A modern reader would react with a great deal of surprise that women and children would accompany an army to the battlefield. Modern armies usually travel far greater distances from home and operate as an all-professional force. These professionals often have organic logistical supports built into the unit that are also staffed by professionals. Ancient armies normally operated under different constraints. Even armies that fought at the Battle of Saratoga from the American War of Independence still had a significant camp following. Ancient battlefields were often just outside their city walls, and rulers constructed armies composed of people who were normally peace-time farmers. With limited manpower, the bulk of the conscripts were needed for fighting, and the remaining camp followers transported supplies, prepared the food, and performed other non-combat functions in order to maximize the use of fighting men. The lack of weapons and armor for camp followers allowed them to carry more supplies than the soldiers could carry, thus extending the operating range. It also sped their march to the destination city. Based on rough estimates from other ancient armies which conclude that non-combatants constituted roughly 33% to 50% of the army,[1] there were an estimated 700 to 1,000 additional women and children following the Nephite army.[2] Since their intent was to garrison a city (Alma 56:15-28), it is assumed that these additional women and children allowed the maximum number of soldiers to perform military tasks, in this case providing scouts as well as building and manning the city walls.And also there were sent two thousand men unto us from the land of Zarahemla. And thus we were prepared with ten thousand men, and provisions for them, and also for their wives and their children. (Alma 56:28)

|

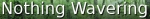

| A special entrance at the Tower of London. I remember seeing the fireplace in the side room and being rather jealous because it was cold and soggy the day visited. |

Additionally, this would bolster the morale of the fighting men, who were presumably conscripted for the duration of the war. Under this assumption, and unlike America’s modern tour-of-duty system, the soldiers stationed on the frontier at Judea would not see their families until their release at the end of the war. The pragmatic solution of bringing the families along not only bolstered morale,[3] but also solved the manpower problem that plagued the Nephite nation (Alma 58:8; 51:11).

The brevity of the text excludes definitive statements, but another possible explanation for the verse is the transfer of loyal soldiers and their families to the frontier as anchors. The Han Dynasty in the first century B.C. established military colonies to protect their frontier and reduce logistical burdens by establishing local farms.[4] Caesar and other early Emperors of Rome granted land bonuses upon the retirement of their soldiers.[5] These soldiers would gain the chance to become local magistrates, and their sons could become patricians and senators.[6] In return, the central government knew that their frontiers contained a greater number of demonstrably loyal citizens capable of organizing and leading local militias in the defense of the Empire.[7] In the case of the Romans these military colonies were a short lived phenomenon in the late Republic until the rise of more limited garrison soldiers in the late 4th century.

In the case of the Nephites, they desperately needed more soldiers in the theater, and there is evidence that they needed more loyal soldiers, as well. The war chapters in this section of The Book of Mormon are replete with references to subversive elements and anti-war factions (Alma 43, 48, 51:13, 53:8-9). In this theater, Mormon also mentions how the enemy gained advantage through “intrigues” on the Nephite side. Thus it is believable that the central government and Moroni sought to bolster a faltering theater with a relocation of loyal soldiers and their families. After the relocation of these soldiers, the Nephite commander felt they were prepared with the addition of these reinforcements.

Women in Combat:

Women and children performed a strategic role in forming armies or defensive colonies and increasing morale as well as lowering the monetary cost of warfare. They also had a close physical and functional relationship to the army for protection and supply. Historically, the breakdown of the front, and particularly the fighting in cities led to women being involved in combat. The Book of Mormon doesn’t record women’s role in combat, but it is still likely, especially in urban combat, or in the camps following the rout of the army. For example, the absolutely horrific account of murder, rape, and rampant cannibalism in Moroni chapter nine helps explain why it sounds as though women and children were included in the army when the Nephites made their final stand (Mormon 6:7). In the abyss of destruction found in Ether 14, the last verse says that “the loss of men, women and children on both sides was so great that Shiz commanded his people that they should not pursue the armies of Coriantumr” (Ether 14:31).[8] Again, the women and children seemed to be included as an integral part of the army. In crusader cities under siege women were recorded as manning the wall with a pot as a helmet.[9] (Some scholars suggest the strange headgear highlighted the otherness of women fighting in a traditionally male domain.) The women normally filled a role as water carries and boosts to morale. Ancient Greeks women and slave would hurl stones and boiling water to kill invading soldiers.[10] Again, note the nontraditional weapons. The women present in crusading camps often faced the enemy when the army was defeated and fled. One account includes a camp follower killing a soldier with a knife. The Muslim victim being killed by a woman was used by writers to make the enemy seem less manly and the knife implied a cooking instrument and not a weapon.[11]

While women helped morale and likely performed vital functions and even fought, the concept of military colonies may have hurt the soldiers and ironically put the women and children in danger. Again, an example from Roman history might help. Towards the end of the empire the government made the distinction between the frontier soldiers and a mobile reserve. Though there are significant problems with relying upon the mobile reserve. The logistics needed to support an army that big means they were fairly spread out, by the time they mobilized and marched to the frontier their enemies would have had as much as 3 months to complete their objectives and withdraw from Rome’s counter strike.

|

| Evolution of Roman arms and armor. |

The inclusion of women and children in Alma 56: 28 is extremely curious in several ways. It suggests that women and children accompanied the army to the field or garrisons consistent with historical practice. This was possibly done for several reasons ranging from money to morale to help the army. But the inclusion of women and children with the armies could have hurt as well. If the army spent too much of their time supporting themselves as farmers and artisans, this would decrease their combat power. If the army failed or a city under siege the women could find themselves on the front lines and having to fight.

[Thanks for reading! I work as a freelance author. If you found value in this work please consider supporting this research using the pay pal button below.]

**********

[1] Donald W. Engels, Alexander the Great and the Logistics of the Macedonian Army (Berkeley: University of California Press, 1978), 13. Ross Hassig, Aztec Warfare, 64.

[2] This assumes that every soldier was married with children, which is impossible to say for certain.

[3] Engles, Alexander the Great, 13.

[4] Graff, Medieval Chinese Warfare, 29. Lewis, Mark, “Han Abolition of Universal Military Service,” in Warfare in Chinese History, ed. Hans Van De Ven (Boston: Brill CO, 2000), 33-76.

[5] P.A. Brunt, The Fall of the Roman Republic: And other Related Essays (Oxford: Clarendon Press, 1988), 264.

[6] John Patterson, “Military Organization and Social Change in the Later Roman Republic,” in War and Society in the Roman World, eds. John Rich and Graham Shipley (London and New York: Routledge Press, 1993), 92-112.

[7] Of course, local leaders could also raise armies to support their own interests. See chapter two in Bleached Bones and Wicked Serpents: Ancient Warfare in the Book of Mormon about the breakdown of central control and the rise of private armies.

[8] See chapter one, in Bleached Bones and Wicked Serpents: Ancient Warfare in the Book of Mormon.

[9] Michel Evans, “Unfit to Bear Arms: The Gendering of Arms and Armor During the Crusades, in Gendering the Crusades, Susan Edington and Sarah Lambert eds, (New York: Columbia University Press, 2002), 54.

[10] John Lee, “Urban Warfare in the classical Greek World,” Makers of Ancient Strategy: From the Persian Wars to the Fall of Rome, Victor David Hanson eds, Princeton: Princeton University Press, 2010), 152-153.

[11] Evans, Bear Arms, 52.

Tuesday, August 4, 2020

Moroni's Tactics and the Vandal War

Belisarius led armies from the Byzantine (or Eastern Roman)

empire in the 6th century AD. He fought the Persians on the eastern

front of the empire and eventually fought a long war to reclaim Italy from

Gothic tribesmen. The subject of interest here is the Vandal war in North

Africa. The Emperor Justinian, taking advantage of a revolt against Vandal rule

and a peace with the Persians, sent Belisarius with a small force of ten

thousand men to attack the formerly held territories of the Roman Empire in

North Africa.

One the invasion landed on the beach; Belisarius marched

towards the Vandal’s capital at Carthage. He ordered his soldiers to pay for

their supplies and forbade them from pillaging. As a result, they had the

support of the people and moved “as if in their own land.”[1] Gelimer, the Vandal king, planned an ambush along their likely route. At Ad

Decimum, Gelimer planned a three-pronged attack. His brother, Ammatas, would

attack the advance of Belisarius from the front. Another force under Gibamundus

would attack Belisarius from the left flank. And Gelimer would use his local knowledge

of roads to take an interior route to attack Belisarius from the rear.

The plan compensated for the division of forces by relying

on the surprise of attacking simultaneously form multiple directions. Unfortunately,

the plan collapsed quickly. The cavalry of Belisarius defeated the flank attack

led by Gibamundus and the latter fell among the fighting. A short time later

the frontal attack led by Ammatas smashed into the Byzantine force. He engaged

the vanguard of Belisarius’ army, but the former hadn’t prepared to attack

Belisarius so far north; as a result, Ammatas had his army spaced out along the

road. The forward units were defeated piecemeal as they marched into the

Byzantines, and then as those units retreated, they affected the next column and

forced them to retreat and so on. His entire force ended up fleeing in a panic

back towards Carthage.

Finally, Gelimer arrived and attacked towards the north at

what he thought was the rear, and already engaged, army of Belisarius. If the

plan had worked, the two attacks by Gibamundus and Ammatus would mean that

Gelimer attacked the rear for a coup de grace like Helamans “furious” attack

upon the rear of the Lamanite army in Alma 56:52 with his Stripling Warriors.

Gelimer routed the screening cavalry (the force that defeated Ammatas earlier),

who then fled to the safety of the main camp of Belisarius. Gelimer regrouped

his forces and stood poised to attack the bulk of the army of Belisarius. He

hadn’t achieved his goal of attacking in the rear for the finishing blow, but

still commanded motivated soldiers flushed with initial victory, while

Belisarius, seemingly under attack from every direction, was trying to reorder

his forces. Yet upon seeing the dead body of his brother Ammatus, Gelimer

paused to assess the situation.[2] The

pause by Gelimer allowed Belisarius to rally his fleeing cavalry, and counterattack

with his entire force. Gelimer fled south, and Belisarius had an open road to

Carthage. He took the city, defeated the resurgent Gelimer and reclaimed North

Africa for the Byzantine Empire.

This story provides several insights into the Book of Mormon. The hook that invited

the comparison was the use of hilly terrain to set up an ambush along an

expected route. In Alma 43 Moroni anticipated the expected Lamanite attack. He

hid an army on east side of the river Sidon behind a hill, and two on the other

side. When the Lamanites crossed the river heading west, Lehi “encircled the

Lamanites about on the east in their rear” (Alma 43:35). Lehi drove them where

they met Moroni “on the other side of the river Sidon” (Alma 43:41). The

Lamanites then fled towards Manti taking another route and “they were met again

by the armies of Moroni” (Alma 43:41). [Insert Nibley Map}

Unlike the defeated Gelimer, the tactics of Moroni were

resoundingly successful. Stuck in the trap the Lamanites responded with fury

that had never been seen before which approached the power of dragons (Alma

43:44). But their tactical advantage couldn’t offset the superior positioning

of Moroni’s forces. The Lamanites could not re-cross the river Sidon with Lehi

on that side (though Alma the younger crossed the ford in the face of a hostile

enemy- Alma 2:27), nor could they retreat towards Manti and then their own

lands, and they could not hack their way through the Nephites to their goal of

raiding Zarahemla to the north.

The comparison reminds the reader that an army is not such an easy thing to maneuver. The hapless General Lew Wallace discovered this on the American Civil War battlefield of Shiloh; Wallace had to march and re-march his soldiers through several different routes because of unclear orders that placed him on the wrong roads; and hence it took him an entire day to reinforce a front several miles away. Gelimer and Moroni had a plan that relied on surprise to compensate for numbers that were likely smaller than their enemies. This was compounded by the fact that their smaller armies were then placed into even smaller sub groups.

Gelimer had to

move three separate forces towards the enemy, and have them attack at the same

time. His force was largely horse based, so maneuvers like this were a bit more

common and easier to pull off than infantry-based armies (and modern readers)

might think. Moroni, in contrast, kept

his infantry-based armies stationary until the Lamanties passed his

positions. This is critical since the

movement of multiples armies to catch a moving army increased the difficulty of

Gelimer’s maneuver. Napoleon was a master and one of the greatest military

geniuses of all time in moving his men in separate columns to engage the enemy

on multiple fronts at the same time to achieve decisive victory.[3] Even

he found it extremely difficult to keep abreast of locations for half a dozen

corps under his command, the need to know their current marching orders and

future locations, the need to modify those orders in relation to the often

fragmentary and conflicting scouting reports concerning a dozen moving enemy

divisions, and the need to move the forces under his command in a way that

brought them into battle in favorable position.[4] The military theorist Carl Von Clausewitz

claimed that Napoleon compared the mass of life or death decisions based on

incomplete information to “mathematical

problems worthy of the gifts of Newton.”[5]

It is no surprise, then, that Gelimer did not catch Belisarius in his snare.

The group attacking from the front and the flank acted too quickly, and only

engaged the leading elements of the army. One attacking group seemed surprised

to see the army. That group entered the battle in fragments and turned what

should have been a decisive surprise into an ineffectual piecemeal attack.

Moroni made sure the entire Lamanite army passed the first

ambush on the east side of the river, which eased the difficulty level of his

maneuver. This also might imply that Moroni adopted a strategy that relatively

untrained foot soldiers could perform. Complex battlefield maneuvers were the

domain of groups like the professional Roman centurions,[6] intensely drilled Prussians, or elite Spartans. The Mongols and other cavalry-based

armies were well trained due to hunting and extensive experience in encircling

and attacking their enemies. But most militaries and most members of the

military in premodern times were part time soldiers impressed into duty during

a crisis.[7] Moroni likely adopted this strategy to compensate for inferior numbers, but

also for an untrained force. Moroni placed his soldiers in a place to succeed

through superior “stratagem” (Alma 43:30) which speaks highly of Moroni’s

skills as a strategist….

Read more in From

Sinners to Saints: Reassessing the Book of Mormon

[1]

Procopius, The Wars of Justinian 3.17.2

[2]

Ian Hughs, Belisarius: The Last Roman

General, (Yardley PA: Westholme Press, 2009) 94. This is different than the

traditional interpretation taken from Procopius in 3.19.3, which laid the blame

at Gilmer discovering his brother’s dead body. Hugh’s claims, and I agree, that

Gilmer discovered the remnants of the battle, and based on its location, and

the location of his dead brother, assumed that Belisarius had already moved

north towards Carthage. Therefore, he paused to assess the situation and

marshal his forces before making the next attack.

[3]

See the Battle of Jena-Auerstadt for a vivid example.

[4] Kristopner

A. Teters, “Dissecting the Mind of a Genius: An examination of the Tactics and

Strategies of Napoleon Bonaparte” Journal of Phi Alpha Theta 9 (2003): 16

(9-21).

[5] Carl

Von Clausewtiz, On War, Michael Howard and Peter Paret trans.,

(Princeton University Press, 1984), 112.

[6]

Victor David Hanson, Carnage and Culture:

Landmark Battles in the Rise of Western Power, (New York: Anchor Books,

2001) 118. He quoted Josephus in describing the professionalism and prowess of

legions: “One would not be wrong in saying that their training maneuvers are

battles without bloodshed, and their battles maneuvers with bloodshed.“ (Jewish War: 3:102-107)

[7]

Morgan Deane, “Experiencing Battle in the Book of Mormon,” Interpreter: A Journal of Mormon Scripture, 23 (2017), 239

(237-252).