This is the 76th anniversary of the Pearl Harbor attack. The nation still mourns and Roosevelt correctly called it a day that will live in infamy. Given the sadness and anger over that attack, the lingering resentment and fallout over the preemptive Iraq War, and the foreign policy challenges ranging from a nuclear North Korea, and aggressive Russia, it is worth looking at what scriptures have to say on the matter.

I’ve written about this topic before. The way that nuclear warfare changes the modern nature of warfare is one of the reasons I started my blog over 8 years ago. At the very least I’m familiar with what Colin Gray called the “demonic” opposition to even supporting the practice. I’ve also contributed a chapter on the subject to the Greg Kofford volume on War and Peace, have a chapter on it in my first book, and discuss the topic in Decisive Battles in Chinese history. (Despite the rhetoric from China as a hapless victim of Western imperialism, since 1949 they have fought offensive, preemptive wars with every one of their neighbors.) I think the discussion can move forward a good deal, and make judicious comparisons to the Pearl Harbor attack.

Against:

The current debate revolves around a handful of scriptures. Opponents of the practice add two scriptures to their anger.[1] The chief captain Gidgiddoni said “the Lord forbid” in response to offensive action (3 Nephi 3:21). And Mormon was supposedly so disgusted with the Nephites desire for offensive warfare that he resigned his command (Mormon 3:11). Yet, Gidgiddoni’s command is likely a strategic observation more than command from the Lord. He likely witnessed disastrous Nephite attempts to root out the robbers before (Helaman 11:25-28), and he used offensive actions as part of an overall defensive posture to maneuver and “cut off” the robbers (3 Nephi 4: 24, 26). Mormon moreover, attacked the Nephites bloodlust, vengeance and false oaths and not their strategic decisions (Mormon 3:9-10, 14). Viewing the Nephites outside of the lens of Mormon’s spiritual denunciations a person sees that the Nephite soldiers actually performed with great skill and élan. A few verses after their disastrous offensive they actually ended up at the same place as they started (Mormon 4:1, 8)! Faced with endemic warfare against a stronger enemy, absent the Nephite’s blood lust and false oaths, this was actually their most justified preemptive action! Of course, none of this excuses their rape and cannibalism, but it does suggest we can assess the effectiveness of their strategy apart from their apostasy. In both cases then, the texts don’t say exactly what their proponents believe that they say.

For:

Yet proponents of the practice face the same problems. Defenders of preemptive war and national security practitioners most commonly cite Moroni’s preemptive attack in support of preemptive war.[2] Though there are strong elements in Moroni’s past that support such behavior and even stronger negative consequences of this policy that remain unexamined. Moroni past includes the Amlicite invasion in the first few chapters of Alma. The Nephites barely held off the attack, but because of its defensive nature they fought at the time and place of the Lamanites (and their Almicite allies) choosing. Alma had to fight his way across the river and was wounded doing so. On top of that, the Nephite crops were destroyed resulting in near famine. Moroni clearly learned from the Amlicite war that aggressive preemptive action prevented disaster.

|

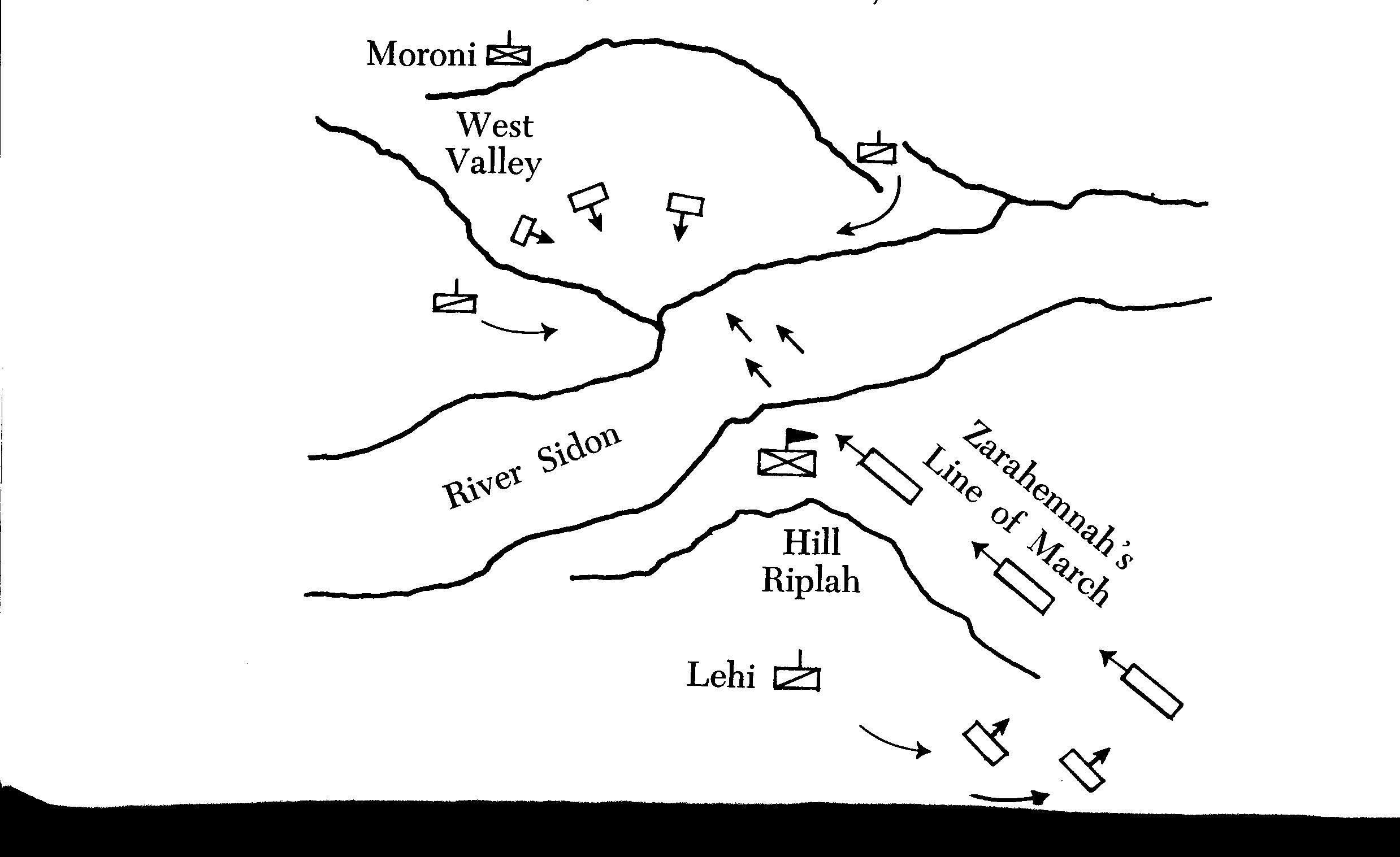

| Since Cumorah tactical map of Alma 43. |

As he prepared an ambush for Lamanite forces, Moroni “thought it no sin that he should defend them by stratagem” (Alma 43:30). Moreover, Moroni preemptively “cut off” Amalickiah, based on the assumption that preventing his escape through military action would prevent a future war. As with his ambush and Zeniff’s scouting, this action is presented without editorial dissent, and it is instead given as part of Moroni’s stellar resume. In the same chapter that describes a period in their history that was “never happier,”[3] Moroni “cut off” the Lamanites living in the east and west wildernesses (Alma 50:11). This occurs during a time of supposed peace, but it could also be described as a lull or “cold war” between the First and Second Amalickiahite War.[4] And Duance Boyce created an entire just war theory out of Moroni’s preparations in Alma 48.[5]

While the text says that Moroni was making plans to secure the Nephites, a careful look at his behavior suggests that Moroni’s aggressive tactics contributed significantly to the start of the last phase of the war and even difficulties in the Book of Helaman. The arguments from the people speaking in towers for example (Alma 48:1), would have been much more effective as only slightly more sinister variations of what actually happened or was about to happen. This includes items such as the possible militarization of the vote (Alma 46:21), and the seizure of lands during what was nominally a time of peace, though it might be termed a lull in one long war (Alma 50:7). Amalickiah would have presented the proposed action to the Lamanite king in the starkest terms. Then it when it actually happened and a flood of Lamanite refugees were entering Lamanite lands, Amalickiah’s position would have been strengthened a great deal.[6]

Unexamined verses:

Yet the debate can move even farther. In the Book of Omni the Nephites fled the Land of Nephi. A few verses later and within a short space of time, and then in greater detail in Zeniff’s record, the Nephites sent scouts to spy on the Lamanites, that they might “come upon and destroy them” (Mosiah 9:1). This verse seems to strongly suggest that the Nephites had already committed to launch a sneak attack, and they simply were looking for the best location. Zeniff changed his mind after seeing what was good in the Lamanites, but with the benefit of hindsight he also admitted at least living among them was overzealous and naïve. The account might also suggests the entire story suggests a need to reassess his description of the other Nephite commander as blood thirsty and austere (Mosiah 9:2.)

The main attractiveness of preemptive war is that a power can attack at the time and place of their choosing, instead of waiting for the enemy to choose the battlefield. This is usual for weaker enemies to surprise and stun their enemies, and also for powerful states to subdue a dangerous and rising power. The Nephites later had to fight the Lamanites when the latter power invaded, suggesting that the preemptive strategy had merits.

Shortly later Ammon recorded, using almost the same words as Zeniff, that the Nephites wanted to “take up arms” and destroy the Lamanites instead of send missionaries to them (Alma 26:25). This repudiation and the fabulous success of his missionary work is commonly cited as repudiation of the supposedly war mongering tendencies.[7]

Yet there remain various unexamined items which undermine this interpretation. Brant Gardner and other scholars discussed how a new king had to legitimize his rule through the successful military campaigns that captured sacrifices, and the Lamanites needed a new king because both Lamoni and his father converted.[8] The innocent victims in the city of Noah from the subsequent attack (Alma 16:3), and the innocent Nephite soldiers who died retrieving them suggest unexamined consequences of Ammon’s actions and an under appreciation of Nephite offensive plans (Alma 28).

The next examples are recorded in Helaman 1. This chapter contains both the dangers against and motivation for using preemptive war. The Nephites faced a serious challenge to leadership and executed somebody for being “about” flatter the people, which may have increased the feelings of social alienation and gave rise to social bandits who are romanticized as brave fighters by the people against a corrupt government. But a few verses later the Lamanites, with both political and military positions filled by dissenters, captured Zarahemla in a quick strike and smite the Nephite chief judge against the wall. These verses provide an example of how the distinction between unrighteous and aggressive wars and increasingly justified preemptive wars is incredibly thin, and becomes thinner with the rise of modern technology.

I wrote down the same ideas many years ago, but I already transcribed the fellow published by Cambridge Press:

[W]hat is different today is the combination of speed and destructiveness; in the [1839] Caroline case a decision had to be taken very quickly by the man on the spot, but although the volunteers carried by the Caroline would have been a nuisance had they landed on the Canadian side of the river, they did not pose an existential threat to large numbers of civilians, or to the colony or...to Britain itself. The stakes today are potentially a great deal higher. 9/11 killed nearly 3,000 people and could easily have killed more; the use of some form of WMD could push the death toll much higher, and there is no reason to think that potential terrorists would be loath to cause such mayhem. The central point is that although "instant, overwhelming....[leaving] no time for deliberation" [the legal precedent established by the Caroline case] sound like absolute criteria they are in fact, and must be, relative terms- a second was, in practice, a meaningless unit of time in 1839, but in 2007, the average laptop can carry out a billion or more "instructions per second."[9]Conclusion:

The final result is something far more nuanced than a couple verses or stories favored by either side. Preemptive war was clearly on the minds of most Nephite leaders. Given how preemptive war fades into the background of both Zeniff and Captain Moroni’s actions, and the lack of clear denunciation of the practice, outside of the spiritual state of the participants, preemptive war is justified. But even though it can be used, the record of the text, and particularly the fallout from Captain Moroni’s changes, suggest that it was of extremely dubious value.

This last point is best application to the Pearl Harbor attack. The devastating Japanese attack seemed dastardly. As I’ve written before, both the Japanese and Chinese have a history of using strategic surprise. After a surprise sneak attack to start the war against the Russians, the Japanese quickly ran out of steam before signing a favorable peace treaty. But in a long war they had little strategic vision beyond a quick strike. They gained a similar advantage against America, but they again showed they had little staying power.

Readers might be wondering why I could spend a significant amount of time on Pearl Harbor day justifying its use. After all, the dead in the USS Arizona still remain there as a reminder of the injustice. The practice can seem like a sucker punch, which is why America still remembers this day so poignantly. Yet Epaminondas and the 3rd century Thebans used the same strategy. Instead of living in infamy, they stopped the yearly invasions from Sparta. He struck at a surprising time and place to permanently alter the balance of power, and free thousands of helots living in near slavery.[10] The practice of preemptive war is simply a tool of statecraft among many. As you've heard in every lame lecture on pornography, tools can be used for varying purposes. A sucker punch for one country can be another’s war of liberation. I mourn the fallen of Pearl Harbor and wish there could be a better discussion of the practice and application of scriptures.

********

[1] This is a representative example: Jeffrey Johanson, “Wars of Preemption Wars of Revenge,” Dialogue: A Journal of Mormon Thought, vol.35, no.3 (Fall 2002), 244-247. https://www.dialoguejournal.com/wp content/uploads/sbi/articles/Dialogue_V35N03_244.pdf

[2] Mark Henshaw, Valerie Hudson et. Al. “War and the Gospel: Perspectives from Latter day Saint National Security Practitioners,” Square Two, v.2 no.2 (Summer 2009.) http://squaretwo.org/Sq2ArticleHenshawNatSec.html

[3] Mormon said there “was never a happier time” during a lull in the war chapters (Alma 50:23). R. Douglas Phillips refers to it as a “golden age” in “Why is so much of the Book of Mormon Given Over to Military Accounts?” in Warfare in the Book of Mormon, ed. Stephen Ricks and William Hamblin (Salt Lake City: Deseret Book, 1991), 27.

[4] Using the terminology of John Welch, “Why Study War in the Book of Mormon?” in Warfare in the Book of Mormon, ed. Stephen Ricks and William Hamblin (Salt Lake City: Deseret Book, 1991), 6-15.

[5] Boyce, Even Unto Bloodshed, chapter 15.

[6] I have significant additional research into the fallout from Captain Moroni’s decisions. It is available upon request in my new book length manuscript, Starving Widows and Evil Gangs: A Revisionist History of the Book of Mormon.

[7] Joshua Madsen, “A Non Violent Reading of the Book of Mormon,” in War and Peace in Our Times: Mormon Perspectives, Patrick Mason, David Pulsipher, Richard Bushman eds, (Salt Lake City: Greg Kofford Books, 2015.) 24. “The mission of Ammon and his brothers to the Lamanites, specifically in defiance of Nephite cultural stereotypes, ultimately demonstrates that acts of love and service can break through false cultural narratives, unite kingdoms, and converts thousand to Christianity where violence could not…In the end, Nephite just wars did not bring peace, whereas those like Ammon who rejected their culture’s political narratives and hatred did.”

[8] Brant Gardner, “The Power of Context: Why Geography Matters,” Book of Mormon Archeological Forum, 2004.

[9] Chris Brown, “After ‘Caroline’: NSS 2002, practical judgement, and the politics and ethics of preemption,” in The Ethics of Preventive War, Deen K. Chatterjee ed., (Cambridge University Press: 2013), 34.

[10] Victor David Hanson, “Epaminondas the Theban and the Doctrine of Preemptive War,” in Makers of Ancient Strategy Victor David Hanson ed., (Princeton: Princeton University Press, 2010), 93-118.

[Thanks for reading. If you found value in this work please consider donating using the pay pal button below.]

No comments:

Post a Comment